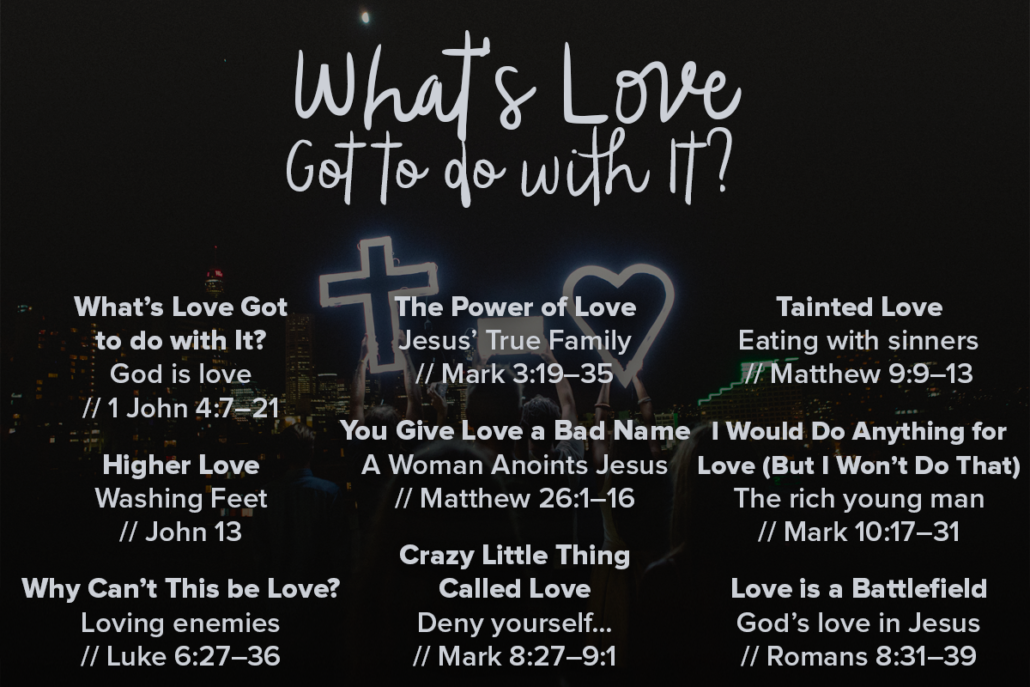

We’re about to embark upon a new worship series at Hope entitled “What’s love got to do with it?”. Apart from the cheesy goodness of using 80’s pop song titles each week, we’ll be looking to explore what we might mean when we say that “God is love.” Here’s an intro to the theme from Matt Anslow…

We’re about to embark upon a new worship series at Hope entitled “What’s love got to do with it?”. Apart from the cheesy goodness of using 80’s pop song titles each week, we’ll be looking to explore what we might mean when we say that “God is love.” Here’s an intro to the theme from Matt Anslow…

—-

What’s Love Got to do with It?

Nowadays it’s common to hear Christians—particularly Christians in our Uniting Church tribe—boil Christian faith down to the requirement to love one another.

“God is love,” we say, as if this resolves any disagreement we might have.

And so, for some, Christianity is really just our way of learning to be more loving, and its core message is not that dissimilar from that of many other religious (and non-religious) traditions. We’re all just working towards a more just society characterised by love, right?

But if we just need to be more loving, why do we need Jesus to tell us that? And if Jesus’ message was simply that we need to be more loving, then why was he rejected and killed? Why would anyone bother executing him for telling people something they already knew?

Stanley Hauerwas, in writing about Jesus and love, sarcastically asks us to “consider how the temptation narrative of Jesus in the fourth chapter of Luke must be read if Jesus is all about love.”

Returning from this desert, the disciples note he looks as if he has been through a very rough time. “Man, you look like you have been to hell and back,” they might say. (No doubt they must have said something like this, for otherwise how do we explain the language of being tempted by the devil?) In response Jesus can be imagined to say, “You are right, I have had a rough forty days, but I have come to recognize what God wants from us. So I feel compelled to lay this big insight on you. I have come to realize that God, or whatever we call that we cannot explain, wants us to love one another. There, I have said it and I am glad I did.”

If this alternative version were true, then we would expect Jesus to return to Galilee and simply go around telling everyone to love one another. But of course it isn’t true, and Jesus does not do that—in Luke’s version he returns from the wilderness and preaches from Isaiah 61, and this results in his neighbours attempting to throw him off a cliff. I guess they didn’t feel loved. Matthew’s version is less dramatic, but no less serious—Jesus returns from the wilderness and begins to preach, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.”

None of this is to say that Christianity is not interested in love. Of course it is! But Christians assume that, apart from Jesus, we don’t actually know what love is. Good thing too, because love can easily become distorted. We look around us and see love portrayed in our culture, and it amounts to little more than strong, passionate feelings for people, things, ideas, and so forth.

These feelings are not bad in themselves, but they hardly amount to the kind of love to which we are commanded in the Scriptures. This is because the love we seek to embody—the love meant when John says “God is love”—is most clearly seen in the cross. It has little to do with how we feel and everything to do with the kind of people and the kind of community we are becoming.

And, frankly, the love we see in Jesus—love that, among other things, calls the world to repent—will not always be viewed as being very loving by the world. This love confronts the powers, challenges sin, forgives enemies, and requires a complete reorientation of our lives.

No wonder this kind of love led to Jesus’ hearers wanting to throw him off a cliff.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!